The old 1950s paradigm that a leader must ignore or suppress her/his emotional urges has been thoroughly discredited over the last 20 years of research. Instead, research shows, time and again, that leaders that are aware of their moods, emotions, and drives, can leverage that competency to drive positive organizational change. While logic and intellect have made our lives easier in many ways—giving us indoor plumbing and high speed internet—they do not motivate people. By placing too high a value on brainpower rather than heart-power, we inadvertently demotivate the teams we lead. Why?

A Leader’s Emotional Field

Because our emotional field acts like an unseen force that either motivates or discourages the teams of people we lead. Our emotions have a profound impact on shaping the perceptions around us. To convey this point, look at the following photo and see if you can answer the question: Which monster is bigger?:

Both monsters are, in fact, of equal size.

Also, look at the following shape. See if you can trace the spiral:

The shape appears to be a spiral, but is, in fact, a series of concentric circles. The visual distortions in both pictures are produced by the backgrounds. In the picture of the monsters, the lines make the monster in the back appear larger. And the background tiles in the image above give the illusion that what we are seeing is a spiral. Our attentions tend to be drawn to the most obvious object, like the monsters, and in so doing, we often overlook the background and its capacity to shape our perception of what we experience.

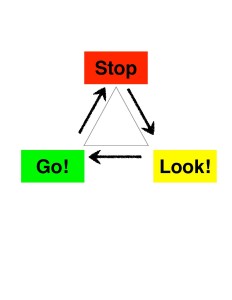

As leaders, our emotions are like those background lines or tiles. Maybe we want our team to focus on meeting their numbers; closing a deal; or putting out a fire. The background of emotion we inject into the achievement of tasks and goals acts as a sort of frame that contextualizes our team’s experience. If, for example, we are scared that our team will not make its numbers, and unaware of the intensity of our fear, we will inadvertently demotivate. Unless we are aware of the emotional fields we create, we, as leaders, will not be aware of our impact upon those we influence. As a result, we will be powerless to wield these unseen forces and silent messages that shape, not only our teams’ experiences, but, ultimately, the destiny of the organizations we lead.

Emotions are infectious in a way that concepts are not. Unlike like logic or analysis, emotion drives action. Without emotion, we are not inspire. Exhilaration, loyalty, fury, and affection give our work lives vibrancy and purpose. Attraction, desire, and enthusiasm draw us toward people and situations, while fear, shame, guilt, and disgust repel us from others. In all cases, emotions act as an all-pervading guide. Emotion has a way of drawing us into almost immediate alignment in a way that thoughts cannot. That's why watching movies in the theater can be more powerful than when we watch them at home. We are surrounded by others’ emotional responses. It is also why stampedes form in stadiums when crowds of people are filled with fright or anger. And we all know what it is like to work in environments where emotions like worry, doubt, and cynicism pervade. Emotional fields like these have an incredible capacity to take the wind out of our sails.

Emotionally intelligent leaders recognize that in order to harness the trust, creativity, and positive will of individuals, groups, and organizations, that is to motivate others toward greatness, he or she must know how to tap into and influence the emotions of those around him or her. Researchers at management the consulting firm, Hay/McBer, have shown that emotional competencies are twice as important in contributing to leadership excellence as are pure intellect and technical expertise . Additionally, the United States Office of Personnel Management oversaw an analysis of the competencies deemed to set superior performers apart from barely adequate ones for virtually every federal job. For lower-level positions, there was a higher premium on technical abilities than on interpersonal ones. As people advanced in their position, interpersonal skills became more important in distinguishing superior from average performance. In other words, it’s more important for leaders to be likeable than it is for them to be smart.

The goods news is that research demonstrates that E.Q. (Emotional Quotient) is learnable. Emotional intelligence is not just something some people are born with and others not, like I.Q. The essential set of skills, the core, in fact, is developed through mindfulness training, which is a simple, age-old, time-tested technique that builds self-awareness and empathy.